A recent (May 10, 2019) news item caught the attention of longtime fans of Mad Magazine. President Donald Trump (R) went after Mayor Pete Buttigieg (D) of South Bend, Indiana, who is seeking the 2020 Democratic nomination for president. The current president unloaded with another one of his infamous Twitter attacks, likening the mayor to Alfred E. Neuman. Buttigieg, displaying a quick wit, did not let this taunt go unmet. “I’ll be honest. I had to Google that,” Buttigieg said. “I guess it’s just a generational thing. I didn’t get the reference. It’s kind of funny, I guess. But he’s also president of the United States, and I’m surprised he’s not spending more time trying to salvage this China deal,” he told Politico. Mayor Buttigieg’s response was clever, at once letting the press know that he can take a joke, and taking two shots at Trump, both calling him old and suggesting that he should spend more time doing his job and less time mocking politicians on Twitter. It was a savvy move by Buttigieg, but I have to wonder: could he really not have known who Alfred E. Neuman is?

How likely is it that Mayor Buttigieg didn’t get Trump’s Alfred E. Neuman reference? We can’t say for sure, but it seems unlikely to me. Alfred E. Neuman is a cultural icon who’s been around for at least twice as long as Pete Buttigieg has been on this earth, and while his popularity has waned a little bit in recent decades, the cockeyed, grinning boy remains widely recognizable. But who is he?

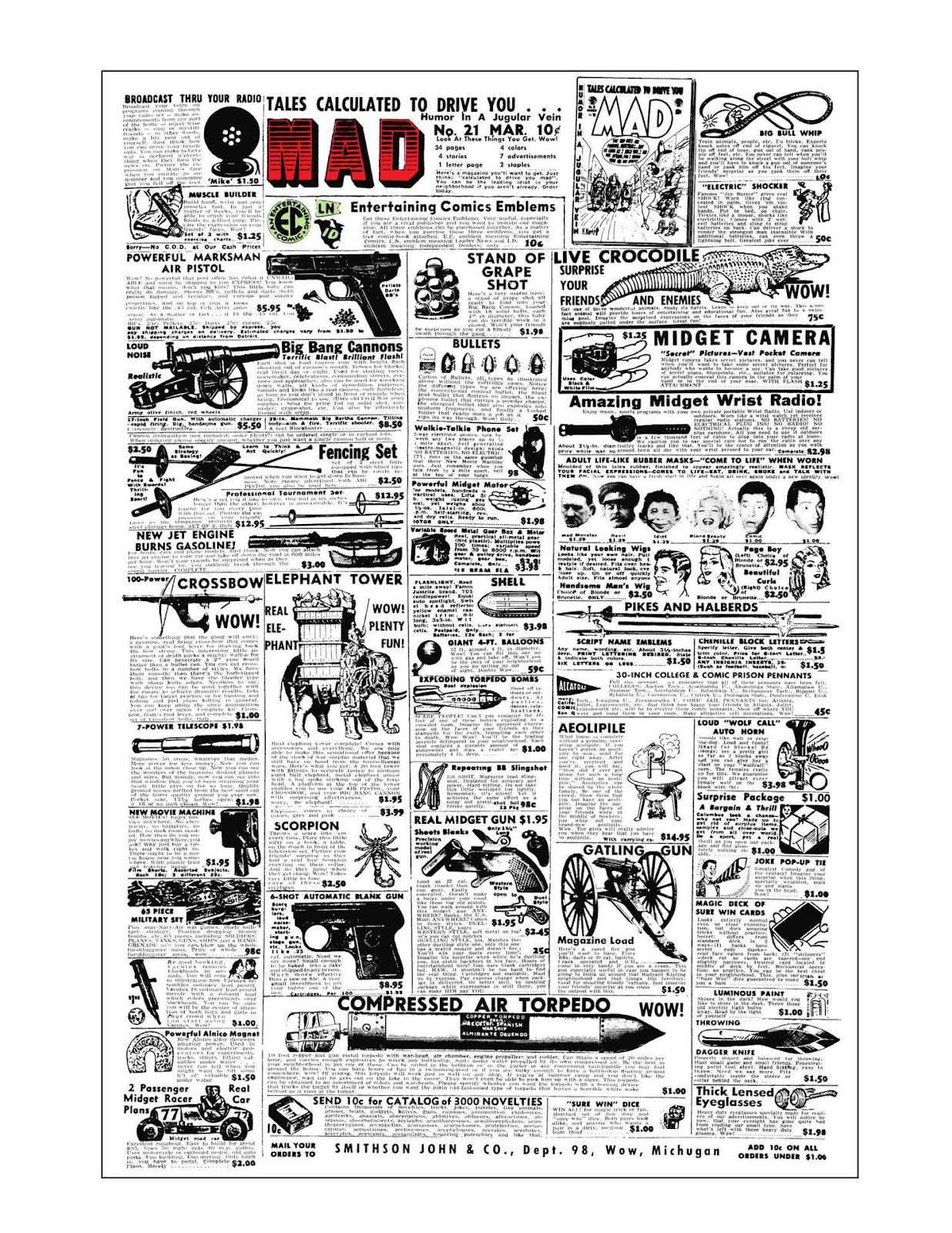

Alfred’s origins have been disputed, despite the extensive research that’s been done on them. What is widely known is that he’s long been the official cover boy for Mad Magazine, gracing nearly every single cover of the magazine from 1956 to the present day. His first appearance in the magazine was earlier than that, back in 1954, in issue No. 21, when it was still published as a four-color comic book. The cover of No. 21 was a parody of mail-order catalogs of the day, filled with cramped writing excitedly talking up the items for sale, represented by clip art. The fake catalog sold howitzers, gatling guns, torpedos, live crocodiles, and other unlikely items. The catalog also included a some face masks for sale, with the recognizable portraits of Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Marilyn Monroe… and this gap-toothed, grinning boy, with the simple tag “idiot” underneath. The “catalog” cover was arranged by writer and cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman, who wrote and laid out the illustrations for almost all of the content for the first 26 issues of the magazine.

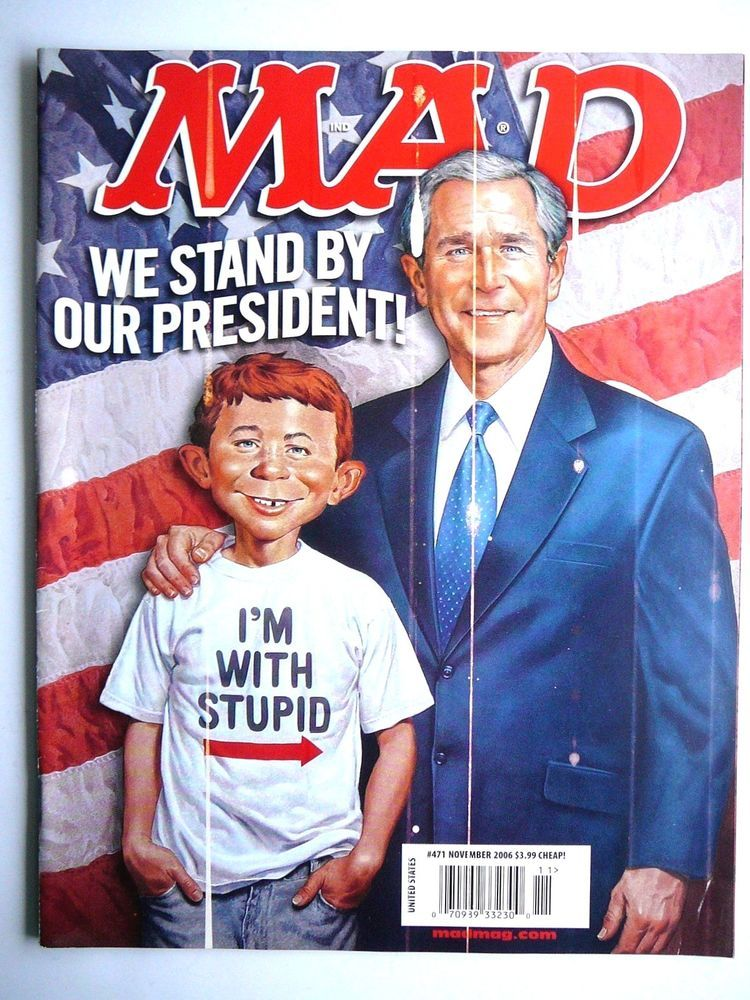

President Donald Trump (left), Alfred E. Newman (center), Mayor Pete Buttigieg (right).

How likely is it that Mayor Buttigieg didn’t get Trump’s Alfred E. Neuman reference? We can’t say for sure, but it seems unlikely to me. Alfred E. Neuman is a cultural icon who’s been around for at least twice as long as Pete Buttigieg has been on this earth, and while his popularity has waned a little bit in recent decades, the cockeyed, grinning boy remains widely recognizable. But who is he?

Alfred’s origins have been disputed, despite the extensive research that’s been done on them. What is widely known is that he’s long been the official cover boy for Mad Magazine, gracing nearly every single cover of the magazine from 1956 to the present day. His first appearance in the magazine was earlier than that, back in 1954, in issue No. 21, when it was still published as a four-color comic book. The cover of No. 21 was a parody of mail-order catalogs of the day, filled with cramped writing excitedly talking up the items for sale, represented by clip art. The fake catalog sold howitzers, gatling guns, torpedos, live crocodiles, and other unlikely items. The catalog also included a some face masks for sale, with the recognizable portraits of Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Marilyn Monroe… and this gap-toothed, grinning boy, with the simple tag “idiot” underneath. The “catalog” cover was arranged by writer and cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman, who wrote and laid out the illustrations for almost all of the content for the first 26 issues of the magazine.

Mad No. 21, March 1955. See the first appearance of Alfred on the right-hand side, toward the top. The catalog text was all written by Kurtzman, who used to write text for actual catalogs like this, earlier in his career.

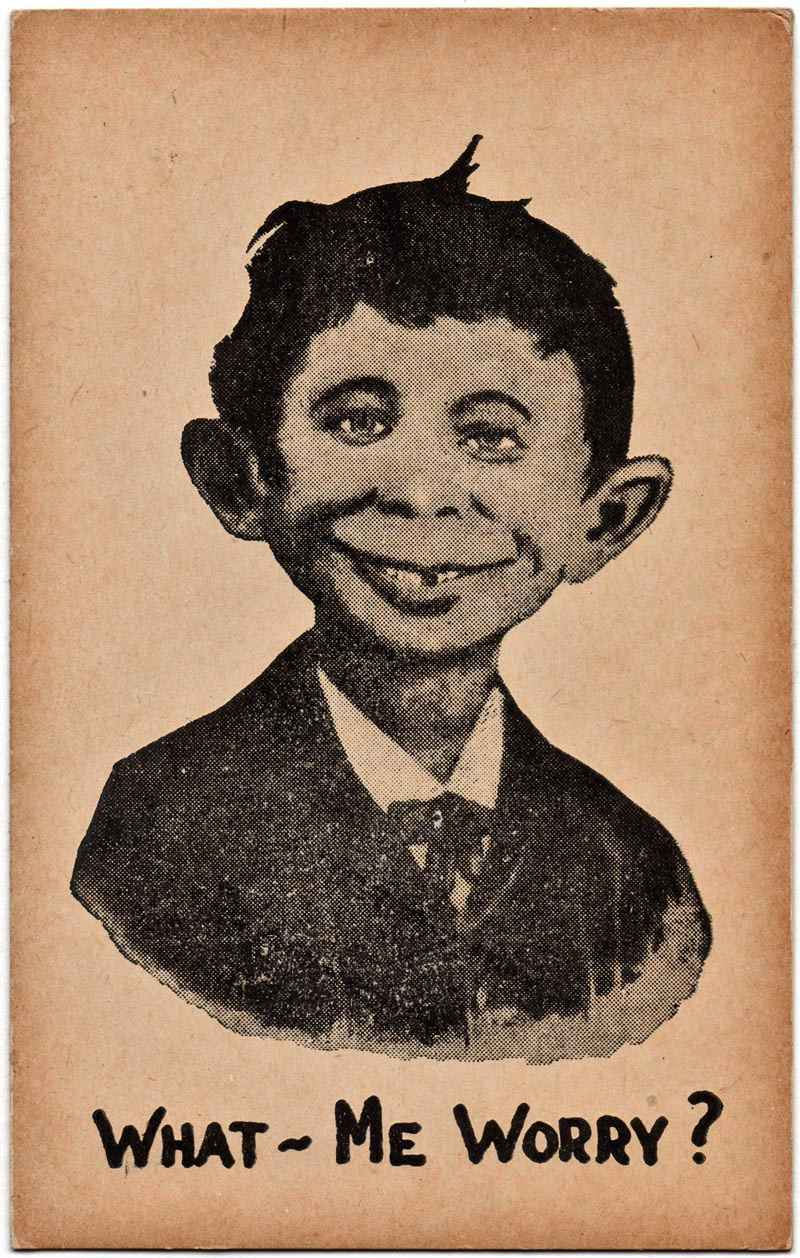

Kurtzman didn’t create any original clip art for this cover, though, including the “idiot boy”. The image that would later come to be known as Alfred E. Neuman was, in fact, one that he had in his office, tacked to a cork board next to his desk. The face was on an old postcard that Kurtzman found funny. Below the face was what would become Mad’s first catchphrase: “What, me worry?” This catchphrase would show up linked to later appearances of Alfred. Alfred didn’t start out as Alfred, however. Kurtzman referred to him sometimes as Mel Haney, and sometimes as Melvin Cowznofski. The name Alfred E. Neuman was a joke name that was used generically by Kurtzman and later Mad writers. Mad borrowed it from Henry Morgan’s satirical radio program So This is New York. Morgan had used Alfred Newman [sic] as a joke name himself, probably in reference to Hollywood composer Alfred Newman. Mad’s version changed the spelling of Alfred’s last name and gave him a middle initial, possibly in reference to former New York Governor Alfred E. Smith, aka “The Happy Warrior”. (As to his middle initial, former Mad editor John Ficarra commented on May 13, “The E is for Enigma.” This is probably not official.) The name Alfred E. Neuman was used as a joke name at first, applied to different characters and referenced generically, but not for long. According to Kurtzman, it was the readers of the magazine who started to refer to him as Alfred, asking questions about their new cover boy in their letters, and the Mad editors had no choice but to bow to public pressure.

The old novelty postcard that hung in Harvey Kurtzman’s office in the mid 1950s. The boy’s face first appeared in Mad No. 21; the now-famous motto first appeared in Mad No. 24, the first issue that was a black-and-white magazine instead of a four-color comic book.

Where did that postcard come from? It turns out that the postcard that Kurtzman possessed was not much of a rarity. This face with the “What, me worry?” motto had been circulating for decades. Lots of people found the face funny, and no one seemed to care about its copyright, if any, in the early days. The idiot boy’s face was reprinted and reimagined in many situations. It was even used as the logo for the short-lived Happy Jack Beverages line of soft drinks in the 1930s.

Previously, it was most common to see this face in advertisements for painless dentists, probably due to the missing tooth. These ads appeared all over the United States, frequently with the motto “It didn’t hurt a bit!” Though popular with dentists, that’s not where Alfred came from, either!

A newspaper ad for a painless dentist in Winnipeg, Manitoba, circa 1910 (left). Art deco advertisement for New York-based Happy Jack Beverages, 1939.

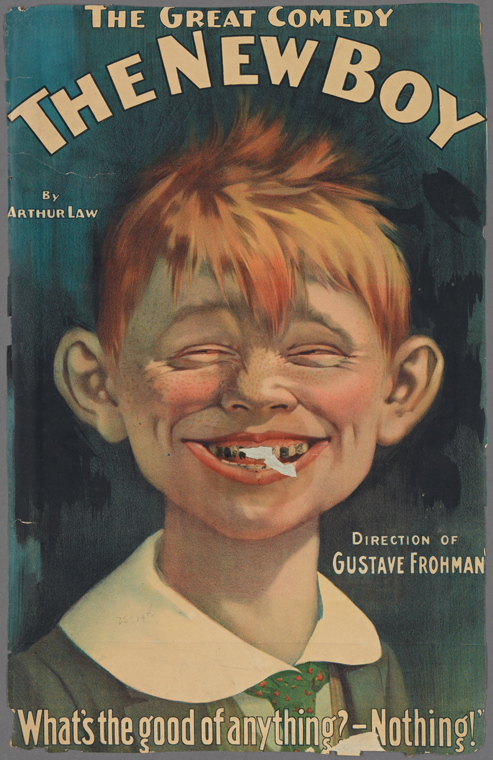

Ultimately, the image comes from the poster for an 1894 Broadway musical called “The New Boy”. The play was a comedy about a man-child, and ran for several months. Copies of the image started to appear almost immediately afterward. Did anyone expect they’d get sued for this image pilfering? What, them worry?

Poster advertising the 1894 Broadway show “The New Boy”. Slightly damaged and slightly vandalized, but no doubt about it: that’s Alfred.

There were lawsuits over the image, but not until well after Mad Magazine had established Alfred as their trademark. It’s not surprising that suits were filed, since the image had been reproduced so much. One claimant to the rights to the image was the Helen Pratt Stuff, the widow of Harry Stuff, who printed over 2,000 of the postcards which he sold and distributed between 1914 and 1920, marketed as “The Original Optimist”. Mrs. Stuff believed she had a case, and had won her case in the lower courts. However, Mad had lawyers working on the case for years, trying to track down the original image. The image from “The New Boy” wouldn’t be discovered until the 1990s, but there had been enough examples of the image tracked down that predated Harry Stuff’s copyright that Mad won the case. Still, it took two years of legal wrangling, eventually settled by the United States Supreme Court in 1967. Mad has enjoyed rights to the image ever since.

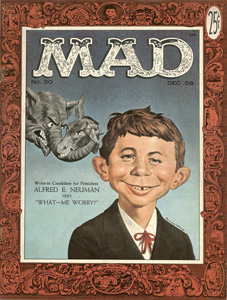

The image that Harvey Kurtzman put in his magazine did become popular with readers right out of the gate, and was quickly adopted, as I’ve already said. But in 1956, after Kurtzman left Mad, the new editor Al Feldstein decided that the image needed to have a little more life to it. Feldstein’s vision was not one of an idiot, but someone more loveable, someone with some life in his eyes, someone who looks like he gets the joke, whatever the joke might be. Feldstein looked for a professional illustrator who was up to the task, and set about interviewing candidates. He extended an offer to Norman Mingo, who had worked illustrating magazines for years. He had interviewed Mingo without revealing what magazine he was representing, like he did the other candidates. When Feldstein told Mingo he would be working for Mad, Mingo reportedly got right up out of his chair and said, “Goodbye.” Feldstein coaxed Mingo back, and as a result got the seminal portrait of Alfred E. Neuman, one which all other images of the boy would be based on.

Norman Mingo’s original interpretation of Alfred E. Neuman for Mad No. 30, December 1956. It has defined Alfred since. Mingo got over his initial reluctance and drew many covers for Mad over the years.

Alfred’s face is one of the most recognizable trademarks in the world. International editions of Mad magazine have exported him to other countries and other languages, as well. The magazine had quite an impact in its first couple of decades. Its impact is arguably diminished, but it’s still around.

In its early days, Mad only dipped into politics very occasionally, preferring to focus more on pop culture and advertising. That changed in the early 1960s, which got the magazine in trouble with those in power sometimes. Mad gets called out as being unfair sometimes, especially when it takes shots at sitting presidents. Mad’s editors and contributing artists take exception to this, frequently pointing out that they’ll go after whoever happens to be sitting in the White House. For the most part, Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, in power during the magazine’s earliest days, escaped its wrath, but pretty much every president since Kennedy has served as a target. A president tussles with Mad magazine at their peril!

Incidentally, Mad magazine was quick to respond to Mayor Buttigieg’s diss.

Mad took pops at Presidents Kennedy, Carter, G. W. Bush, Obama, and Trump… and no doubt at whoever comes next.

Comments