In Old English and Middle English

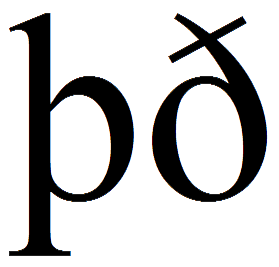

there were two letters that we don’t use today: Þ and Ð (called thorn

and eth—written in lowercase as Þ and ð). Thorn was the hard th

sound, like you hear in the word then; eth could be used for the soft th

sound, as in thin, but could also be used for the hard th.

Eth slowly disappeared from English writing, falling out of use by the year

1300. Thorn lasted a while longer, maybe another century, but its demise

was hastened by the popularity of printing. Signs and handbills were

printed on paper with sets of wooden blocks. The best blocks came from

Germany and Italy, where the languages don’t have the th sound at all,

so these sets included no thorn or eth blocks. To fill the need of the

missing thorn, printers would just use the letter Y instead. This is why

you would often see medieval signs like “Ye Olde Bakery”. This is just

because the printers couldn’t print “Þe Olde Bakery”! Of course they

could paint signs with any letters they wanted, but as printed material grew

more common, so did ye. If you lived in medieval times and could

read, you knew this was pronounced the way we pronounce the today.

The letters eth and thorn are

still used in modern Icelandic.

Þat’s all, folks.

Comments