|

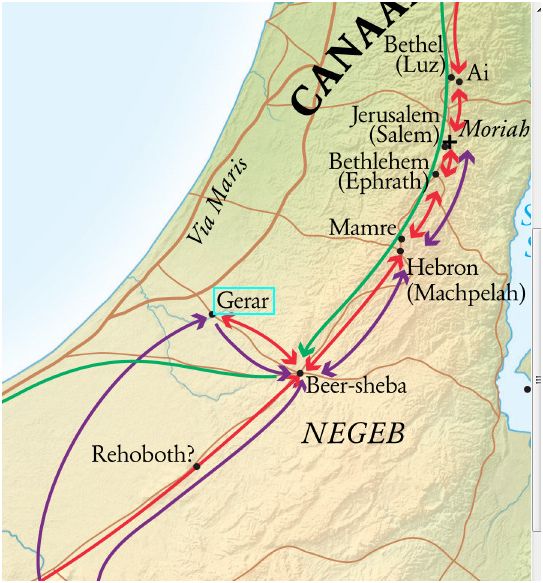

| Here's a map, in case you're having as much trouble following these people around as I am. |

Isaac had a dream. In it, God told him he shouldn’t go to Egypt

or to anywhere else, and that he should stick around. If he did, God would tell him where he should go, and what he

should do so that he would be heaped with blessings, and that his descendents

would be, as well, and any country where they would choose to live in the

future would be happy to have them. God

told him to go to Gerar, where the Philistines were. Gerar wasn’t a great option—it was no better, in fact, than where

he’d been living before. There was a

drought everywhere, so moving on was tempting.

The king of the Philistines at

Gerar was, of course, Abimelech. This

might have been the same King Abimelech whom Abraham ran into; this might have

been a different one. Since the name

Abimelech translates roughly as “my father was the king,” it’s possible that

this Abimelech was just another one in a long royal line of Abimelechs. Like Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah

decided to settle in to Gerar. And like

Abraham, Isaac told everyone that Rebekah was his sister, not his wife, because

he figured everyone would kill him for her if they knew he was her husband,

because of course they would. Once it

was well established that Rebekah and Isaac were siblings, they started acting

like siblings by groping each other in public.

Abimelech himself looked out his window and saw this and called Isaac in

to talk to him.

“That has got to be your

wife!” said Abimelech. “I saw you two

in the clench!”

“Yeah, okay,” said Isaac, “you

got me.”

“Why did you lie to us about

that? And why did you do such a poor

job of covering up your lie?”

“Well, I didn’t want anyone to

kill me for her,” confessed Isaac.

“But what a terrible thing for

you to do to us!” admonished the king.

“One of our men could easily have slept with her, and then the guilt

would have been on his head!”

“Well, no,” Isaac pointed

out. “See, we’re married, so she isn’t

sleeping with anyone else.”

“How do you figure that’s any of

her business? Who sleeps with whom is a

man’s department. Trust me on this; I’m

a king.”

“But isn’t that rape?” asked

Isaac.

“That’s enough of your elitist

liberal backtalk. Look, just to make

sure we’re all safe, no one is allowed to touch you or your wife, or they risk

penalty of death. That’s a royal

decree. Now go in peace. And,” added Abimelech with a wink, “remember

to notice which females are wives and which are… not.”

Isaac set up his farm, which did

extremely well that year, despite the drought.

The Philistines were a bit envious of this, so they started to fill in

the wells that Abraham’s servants had dug years ago, because too much water

might spoil the drought. They told

Isaac that he was doing too well, so he’d better get out of town. Isaac found a nice tax shelter in the Valley

of Gerar, where Abraham had farmed. He

opened the wells up (a secret to farming that the Philistines didn’t seem to

understand). As he reopened the wells,

the local herdsmen fought him for them, and he gave them names to commemorate

these quarrels. When he found one that

the herdsmen didn’t fight him over, he called it Rehoboth, because he liked the

name, and no one could stop him from calling it what he wanted.

The competition with the herdsmen

must have gotten too hot, because Isaac decided to pull up stake again and head

up to Beersheba. When he got there, God

showed up and said,

“I am the God, the God of your

dad,

Don’t be afraid, things aren’t

bad.

You’ll do well, so will every

last kid

Of yours, because of what Abraham

did.”

Isaac then made an altar and said

God’s name, which you’re not supposed to ever do, except sometimes.

Abimelech went to Gerar to meet

with Isaac. Since it was just a

friendly social call, he brought his army with him.

“Why are you paying me a call,

even though you hate me?” asked Isaac.

“We think God likes you, so we

decided to like you, too,” explained Abimelech. They decided this was reason enough to sign a treaty and have a

party to celebrate it, because why not?

The next morning, they promised to keep on being nice to each other, and

Abimelech and his army left. Afterward,

Isaac’s servants struck water while digging a well.

“Let’s call the well Sheba,” said

Isaac.

“Why?” asked the servants.

“Because if we don’t, it won’t

make any sense when we call the town Beersheba, now will it?” snapped

Isaac. Too afraid to get on Isaac’s

nerves any further, the servants let the matter drop, and accepted the town’s

new name.

Comments